The Hamlet Chicken Processing Plant Fire and What We Can Learn from It

by Siegfried Isidro-Cloudas on Sep 8, 2022 10:30:00 AM

September 3rd marked the 31st anniversary of the Hamlet Chicken Processing Plant Fire, the second most deadly industrial disaster in the history of North Carolina. It is important to look back on the tragedy to honor the legacy of those who perished and to make sure that, as engineers, we do everything possible to prevent a similar event from happening. As we look back at the events of the fire, we will look at the history of the plant, what led to the incident, and what lessons were learned in the aftermath of the fire.

Image from waymarking.com

Imperial Food Products Chicken Processing Plant

The Imperial Food Product chicken processing plant was owned by Imperial Food Products Incorporated (also known as Imperial) which resided along Bridges Street in Hamlet, North Carolina. The facility was purchased by the corporations’ founder, Emmett J. Roe, in September of 1980 and was previously the location of the Mello-Buttercup Ice Cream plant, which had since been largely decommissioned. After the purchase, the 21,300 square foot facility was vastly renovated and expanded to 37,000 square feet prior to initiating operations at the site.

Despite multiple changes to the facility requiring building permits, Roe never applied for them and proceeded with construction. Additionally, Roe did not register the plant with the local labor department, nor did he apply for a business license for the facility[1]. The facility was also not registered with the appropriate tax authorities, and as such no property tax, water, or sewage bills had been paid to the local government by the time of the accident.

The Hamlet facility, despite being one of several facilities owned and operated by Imperial Food Products Incorporated, was the primary focus of Roe and his son/operations manager, Brad, by the 1990s. Over the years the Hamlet plant was the subject of many safety concerns. In 1980, 1983, and 1987 there were several small fires in the plant, yet none resulted in safety inspections. In fact, the portions of the facility operated by Imperial had never undergone a workplace safety inspection despite OSHA inspectors visiting the site several times to examine spaces leased to Mello-Butter, the plant’s former owner. One of the fires from this period disabled the fire sprinkler system at the site and was never subsequently repaired. Though the fire sprinkler system had fallen into disrepair, an automatic carbon dioxide fire extinguisher and hood were installed at the facility after the 1983 fire.

Safety guidelines regarding fires at the Hamlet facility were lax at best. Hiring orientations for line workers only partially covered safety guidelines and did not cover fire safety. Following food safety inspections that found large numbers of flies in or around the building, several exterior doors had been locked from the outside and were to always remain locked. Additionally, a shed structure was built around the facility dumpster and trash compactor, once again without a permit, with an interior door that open into the structure. Emmett Roe directed a maintenance worker to padlock exterior doors to keep workers from stealing chicken. The shed and locked doors were approved by USDA, though they violated workplace safety standards.

Other exits at the facility were also locked or obstructed, including a marked fire exit. Many employees did not know that these doors were locked, with this fact being known only by a handful of employees. The facility also did not have a fire evacuation plan, only had a single fire extinguisher, and had no fire alarms. The lack of fire alarms and the locking of doors not only violated OSHA rules, but also violated North Carolina State law.

Exacerbating this issue, the city of Hamlet did not have the funds to appoint a fire inspector to examine commercial buildings in the jurisdiction to ensure compliance with the North Carolina fire code. Additionally, the Hamlet Fire Department had no contingency firefighting plan for the Imperial Hamlet plant.

The Fire of September 3rd, 1991

In the months prior to September, one of the hydraulic system lines of a conveyor belt at the Imperial Hamlet plant had begun to periodically leak. This line resided in proximity of a Stein fryer, and the operations manual advised for the equipment’s heat sources to be deactivated prior to any process or operation that would require the handling of flammable liquids in proximity of the fryer. Ahead of the needed repair, the plant’s head mechanic, John Gagnon, had asked Brad Roe for funds to purchase new lines and connectors to fix the leaky line. This request was denied, and the crew was instructed to improvise the repair with spare parts (a common money saving practice by Emmitt and Brad Roe had used in operating this facility). Over the Labor Day weekend, a maintenance crew worked to repair the line using a spare line that was longer than the standard part.

At 8:00 AM on Tuesday, September 3rd, 1991, the first shift of 90 workers reported for work on the production lines of the Imperial Hamlet plant. Around the same time, the maintenance workers reconsidered the repair that had been done to the hydraulic line, deciding to shorten it with a hacksaw and reconnect it using an improvised connector. Due to the induced downtime of deactivating the fryer and reactivating it, coupled with the fear that this would anger Brad (the plant operations manager), the maintenance crew decided against deactivating the fryer while changing the repair and testing the line.

At about 8:15 AM, the maintenance crew turned on the conveyor line and the improvised connector failed, spraying Chevron 32 hydraulic oil onto its surroundings. Some of this fluid landed on the heating lines for the adjacent cookers and vaporized, with the vaporized fumes entering the flame of the cooker and igniting. The hydraulic line pumped between 50 and 55 gallons of Chevron 32 into the fire before an electrical failure shut off the hydraulic system. The fire continued to grow, fueled by a combination of hydraulic fluid, chicken grease, and soybean-based fry oil (despite the fry system being under the previously installed carbon dioxide suppression system and hood). Soon after, the blaze spread to a nearby natural gas regulator, which then failed and began to fuel the fire with natural gas as well. Within two minutes, the plant was engulfed in flames. Within minutes the fire severed power and telephone lines to the building and burned a hole in the roof, and the building began to flood with smoke and carbon monoxide.

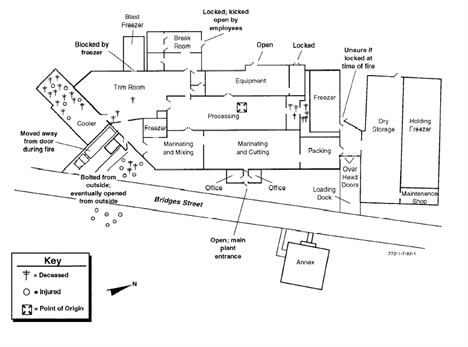

Due to the construction and configuration of the facility, primarily open spaces to allow forklift access that had minimal barriers, smoke and heat spread rapidly through the facility. The fire effectively split the facility in two, with workers in the marinating and packing rooms being able to flee through the unlocked front door and those in the processing and trim rooms being forced to retreat towards the loading dock, dumpster, break room, and equipment room. At the time of the fire, a delivery truck was idle in the loading dock with a driver asleep in the cab, blocking exit through the loading dock opening. A nearby door to the loading dock was obstructed by an outdoors dumpster. Many of the remaining exterior doors in this region of the building remained padlocked from the outside. Despite the attempts of the workers to make openings in the breakroom and loading dock, as well as trying to kick out the padlocked doors, no exits could be made. After their attempts, some workers retreated to a nearby cooler for safety while other stayed near the loading dock.

As the fire broke out and spread, Brad Roe attempted to contact the fire department, but failed due to the severed telephone lines. After his attempts to call the fire department, Brad drove to the Hamlet fire department to alert them of the fire, arriving at the fire department at 8:22 AM. Only two firefighters were on duty at the time, and upon arriving at the Imperial Hamlet facility at 8:27 AM the fire Captain, Calvin White, sent a call for aid to the Rockingham Fire department due to the severity of the fire. At this time only 20 of the 90 workers at the facility were outside, of which 3 were already dead.

Seeing the smoke from the facility, several neighboring residents arrived on scene and awoke the truck driver idle in the loading dock. Several Hamlet municipal workers who arrived on scene managed to remove the dumpster to create an escape route for workers. A maintenance worker on the north of the building managed to kick out an exterior door, allowing for 10 workers to flee the building.

As more firefighters arrived on scene, attempts were made to enter the building and contain and control the fire. Despite being forced to fall back initially, the fire suppression team was able to bring the fire under control by 10:00 AM. Search and rescue operations began on site around 8:45 AM and ended when the final casualty was recovered at 12:20 AM. In total, 25 workers died and 54 were injured. Nearly all the dead were impoverished and undereducated workers from the neighboring community, half of which came from the African American community of Hamlet. This conflagration was the second deadliest industrial disaster in North Carolina’s history.

Floor plan of the Imperial Food Products Hamlet Facility, Image from United States Fire Administration USFA Report

Learning from the Legacy of the Incident

Many lessons can be learned from the legacy of the Hamlet Chicken Processing Plant fire. The first and foremost lesson is the importance of following code and regulations. Despite the approval of the USDA, the locking of the facility doors violated workplace safety standards and had deadly consequences. Additionally, the lack of inspection by OSHA and fire inspectors let many hazards remain undetected, exposing the workers and facility to risk. Had these hazards been identified by inspection and subsequently addressed through the appropriate renovations, it is plausible that lives could have been saved and perhaps the fire could have been contained. Additionally, according to the USFA report[2], no one knew to what codes the original Imperial Foods building was built to, as the building was built in the early 1900’s. An inspection of the building and updates to bring it up to the applicable code requirements could have reduced the risk of a deadly fire and could have saved lives. It is imperative that we do our best to ensure that we follow the appropriate codes, design standards, and regulations when designing facilities, and when we find violations that we elevate them to the appropriate officials for inspection.

The next lesson that can be learned is the importance of an up-to-date, functional, and code complaint fire protection system. When the fire broke out at the Hamlet plant, many of its fire sprinkler systems were not functional and could not help to contain the fire. While the carbon dioxide fire extinguisher and hood system operated as intended, they could only slow the progression of the fire to the fry oil. Also, if the plant had shut off valves installed on the hydraulic lines serving the conveyor system, it is possible that the fire would have not been supplied with enough fuel to spread. Additionally, the lack of a plant evacuation plan and a lack of a contingency plan with the local fire department increased the deadly risk of the fire. Had the facility had fire alarms, adequate and clear routes of egress, as well as regular fire drills, the fire may have been less deadly, and lives may have been saved.

Another lesson to be learned is that repairs and renovations of systems should be done by trained personnel, in accordance with the system operation manuals, and using appropriate components. The direct cause of the fire was the failure of an improvised connector in conjunction with a disregard for the operation guidelines for the Stein fryer. Had the correct parts been used and the fryer been shut down, the specific causes of this fire could have been avoided.

There are many more lessons to be learned from this tragedy, many of which are outlined in the USFA report on the fire. For further reading on this incident, see the USFA-TR-057 Chicken Processing Plant Fires report on this fire.

[1] At the time, North Carolina law required industrial businesses to apply for licenses to operate. Additionally, any business with 11 or more employees was required to register with the North Carolina Department of Labor and the United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

[2] US Fire Administration/Technical Report Series, Chicken Processing Plant Fires, USFA-TR-057, Page 6, https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/tr-057.pdf

About the author

Siegfried Boyd Isidro-Cloudas is a Mechanical Engineer working out of Burlington, VT, who joined Hallam-ICS in April of 2022. He graduated from RPI with a B.S. in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering in 2017, and has been working in the field of mechanical MEP design since 2017.

Read My Hallam Story

About Hallam-ICS

Hallam-ICS is an engineering and automation company that designs MEP systems for facilities and plants, engineers control and automation solutions, and ensures safety and regulatory compliance through arc flash studies, commissioning, and validation. Our offices are located in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Vermont and North Carolina and our projects take us world-wide.

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

7 Steps to Complete a Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA)

I’ve Completed My DHA–Now What?

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think