Engineering Ethics and Competency

by Jeff Babineaux, PE on Apr 11, 2024 10:30:00 AM

The National Society of Professional Engineers doesn’t want me to be licensed as an Electrical Engineer. It’s not like I did anything wrong. The NSPE insists that all professional engineers are just that: a PE, and that certification in a specialty doesn’t make them more capable than one who does not have the certification. Does this mean that I can prepare and seal a design for a custom air handling unit, modifications to medical equipment, or ventilation systems? Well yes, and no. Let’s talk about what makes a professional engineer competent, who decides, how they decide, what happens when you impose a system for making this decision, and why it’s important to ask these questions when there are no right answers, but definitely some wrong ones.

Competency: On Ethics and Professional Development

To properly talk about competency, it’s important to separate the ethical requirements of competency from continuing professional development. The question of “Are you qualified to design this building electrical system?” is different from “How much do you know about building electrical systems?” While the first is only ever “yes” or “no”, the second could be measured in degrees, and it’s easy to propose that there is some incremental level of the second that would not qualify you to say yes to the first. “Sure, I know what a panelboard looks like. No, I should not seal that drawing.” While the incremental definition is important to growing as an engineer, we should set that aside for now. Let’s come back to it when we talk about systems for determining competence.

Once we establish that a person is able to design something as a professional engineer, and by extension apply their professional engineering seal, that person can confidently proceed with the design. And I mean the whole design.

On Responsible Charge: Yeah, the Whole Thing

Understanding the principles of engineering related to a design naturally has its limits. I don’t need to know the design of a chip in an electronic breaker to specify it, but I do need to understand its function as it relates to the overall system to take ownership of the engineering design. This ownership is set out in model law as “Responsible Charge” by the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES) and is adopted in varying forms by state licensing boards. I talked about ownership at length with some coworkers about where that line is drawn, and I never got to a good rule of thumb for what a minimum level of ownership would constitute responsible charge. I agree when he proposes that a breaker manufacturer controls the principles of its equipment operation. NSPE, however, published a case study where leaning too heavily on a vendor can constitute a conflict of interest. (NSPE 1) How much outside help, then, is too much? How does this relate to the pooling of expertise of an engineering team where not all engineers are licensed in all fifty states? When does a manufacturer relationship or lunch-and-learn cross over from preference to conflict of interest? These questions are not flippant or rhetorical. We need to keep asking ourselves these questions as we grow.

Competence established! Yeah? Says Who?

Just because the NSPE says that engineers are not limited to their own field, we are still bound by the rules and laws of the board that issues our engineering license. While some engineers may have only a single board to answer to, lots of us need to check with each state when asking what counts. I know that’s a long round-about way of saying it depends, and I know as engineers we say “it depends” so much that I’ve considered adding it to my engineering seal. However, exploring these issues in the context of the current situation every time is what makes us great at what we do.

I’m from Louisiana. You might have guessed from the ‘x’ at the end of my name. According to the Louisiana Board, LAPELS, every engineer is assigned a discipline based on the PE exam that we took. BUT (and there’s always a but), the state board specifically mentions in their definitions that “[t]he practice of engineering in a discipline other than that in which the licensee has been listed will not be considered as evidence of gross incompetence, provided the licensee is otherwise qualified by education or experience.” (LAPELS) North Carolina’s professional Engineering Board, NCBELS, does not have the same assignment of discipline, and only requires that engineers not seal work outside of their area of competence. (NC OAH) Ultimately, the first definition of competence comes from within. Like so many boards who rely on professional engineers to decide if something qualifies for professional development hours credit is acceptable, we need to assess our own competence. But how?

Proposed Systems for Evaluating Competence

NSPE and the Broad Definition of Engineering

This method sounds like a social media challenge to come up with your Harry Potter movie name, but a lot of what we know about engineering is preserved here. The code of ethics that they publish will no doubt look a lot like the code of ethics adopted by each state board, because they advocate for what the field of engineering looks like, for students and professionals alike.

NSPE’s stance against prohibiting licensing by engineering discipline appears unwavering, with position statements released in 2009 and 2010, and most notably their efforts to remove language that separate structural engineers from the rest of us. (NSPE 2) I’m nervous about that, as my limited experience with the nuance of building structural design as it relates to calculations in ASCE overwhelms me. It makes me wonder who would decide for themselves that they’re comfortable with it without passing some separate examination, but at the same time I’m very comfortable with a lot of designs where parts of mechanical and electrical engineering overlap.

By NSPE’s guideline, design what you will, just make sure you know what you’re doing. As Jiminy Cricket or Marvin Gaye says, “let your conscience be your guide.”

Sticking to Your Degree

For young engineers, the limitation of your degree that got you to your exam might carry with it a comforting restriction. Like bumpers when I was a kid at the bowling alley, I spent four years (okay, six) getting a degree in electrical engineering to take a test on it, and NCEES tested me on that body of knowledge, guided by other engineers who have been licensed before me. If it was on the test, and I passed it, I have a metric by which someone else told me that I know enough. The example above where LAPELS lumped me in with the other electrical engineers was a good start, but most of them did not spend their first four years out of college in the manufacturing of modular electrical equipment enclosures for industrial locations. This highly specialized market means I became comfortable with some mechanical details, but I didn’t know enough about renovations or commercial lighting design until after getting my license, and then working under someone who gave me an introduction to these concepts.

Sticking to our degree opens us up to some level of liability when fields like electrical and mechanical engineering are so broad. We should be able to grow and build these skills, designing systems that effectively prioritize the safety, health, and welfare of the public, but a degree in a discipline, in and of itself, doesn’t satisfy this measure of competence for me.

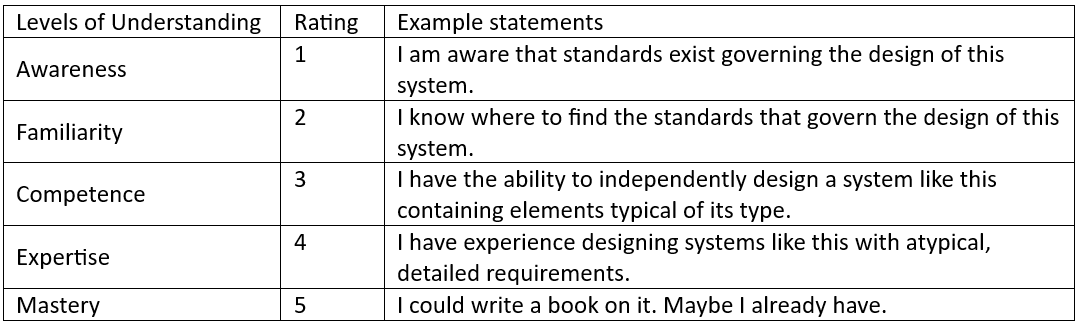

The Competency Matrix

This brings me to a competency matrix. This method involves really digging down and asking ourselves what skills we have, what level of understanding we have of each, comparing that to the skills necessary to complete a design, and then answering ‘yes’ to all of these. We do this at some level when we are asked to perform a task. Maybe there’s no reason to get paperwork involved, but considering at some level all the knowledge required should be a fundamental starting point of accepting ownership of a design.

An example of a competency matrix is one that is granular down to each of the design tasks required. Even if you don’t yourself assign circuits to equipment and add up their total loads, for example, this might be a necessary skill in the determination of creating a building electrical distribution design. Once the skills are listed, they could be qualified with a level of knowledge including measures such as “awareness”, “familiarity”, “competence”, “expertise”, and mastery”. An example for gauging this metric is below:

One advantage to a competency matrix is that it shows consideration of each of the skills required to perform a design, and then reflection on the level of mastery of each. If a significant portion of the design requires a skill where the engineer has only casual awareness, a matrix offers the opportunity to step back and decide on growth, or to consider another engineer who could provide a more complete responsible charge.

Limitations of Imposing Systems for Determining Competence

No system is perfect when it comes to the ethics of safeguarding the public. Each system is just one way of measuring if we believe we are up to the task. When one takes NSPE’s advocacy cause to heart and accepts the full burden of an otherwise unrestricted measure, one must be hyper aware of their strengths and weaknesses, and open and honest when asked to take on a design. Allowing our education or an engineering exam to determine the breadth of our knowledge leaves us open to edge cases in our own discipline. A tool like the skill matrix can be developed for professional development, and skills necessary for the completion of a specific project could be lumped in with whatever seems to closest fit, or the development of the matrix could be pushed off on a larger organization, bloating the decision by trying to make it fit into a bigger picture. In all cases, the question of ethics is too complex to always be answered by a spreadsheet or a rule of thumb.

Ultimately, we need to know what we know, and know what we don’t know. Otherwise, we put others at risk, and we fail to live up to the code of professional conduct we agreed to when we took on the title of Professional Engineer. When these failures become apparent, each governing board has their own method of telling you what you missed.

Consequences of Acting Outside of Your Area of Competence

We pride ourselves here at Hallam on transparency, and this openness is part of what makes conversations like this possible. Part of what is so rewarding about being a North Carolina professional engineer is how its board views transparency. NCBELS publishes a newsletter every year, listing the board’s disciplinary actions at the end. These have been helpful as a growing engineer to recognize patterns. The board has disciplined four people in the last three years for performing services outside of their area of competence. While the details of the cases are not readily available, it’s important to note that where the licenses were not surrendered, the individual was then restricted by the board from practicing in that particular discipline. (NCBELS 1, NCBELS 2, NCBELS 3) No, you are not limited by default to a single discipline. Until you are.

Conclusion

All engineering work should be performed with the safety, health, and welfare of the public as the first priority. It’s the first fundamental tenet of the code of ethics set out by NSPE, followed only by the requirement to operate only within one’s area of competence. This is restated in the engineering rules of professional conduct here in North Carolina, and in many other states. There are no easy answers out there for what decides competency, but assessing our own ability to perform the work should always be approached with transparency and humility. Even as we grow into new roles and expand our expertise, our readiness to accept ownership of an engineering design that stretches our expertise should be weighed against the safety of all.

References

LAPELS, https://www.lapels.com/docs/Laws_and_Rules/Board_Rules.pdf

NCBELS 1, https://www.ncbels.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Fall-2023.pdf

NCBELS 2, https://www.ncbels.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Fall-2022.pdf

NCBELS 3, https://www.ncbels.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fall2021.pdf

NSPE 2, https://www.nspe.org/resources/issues-and-advocacy/action-issues/licensing-engineering-discipline

About the Author

Jeff has a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from Louisiana Tech University. Prior to coming to Hallam-ICS, Jeff had 7 years of experience working in prefab construction for mechanical and electrical buildings and skids. He holds a professional engineering license in multiple states, participates in all phases of the project design from concept through construction, and cooks a mean gumbo.

Read My Hallam Story

About Hallam-ICS

Hallam-ICS is an engineering and automation company that designs MEP systems for facilities and plants, engineers control and automation solutions, and ensures safety and regulatory compliance through arc flash studies, commissioning, and validation. Our offices are located in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Vermont and North Carolina and our projects take us world-wide.

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

Designing for Plastic Pipe Expansion

How Extracurricular Activities Boost Engineering Education

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think